The Greater Mekong Region’s forests are integral to many different social, cultural, economic and political perspectives. For example:

- trade in forest products is of high importance to the economy in the region1

- government policies that regulate forest resources can have major impacts on indigenous peoples, who have traditionally been custodians of forest resources2

- the region’s biodiversity is highly dependent on the habitats forests provide and is under increasing pressure3

- growing populations mean that demand for competing land uses such as agriculture and new housing place greater pressure on forest resources4

- the ecosystem services that forests provide, such as regulating water supplies, mitigating climate change and enabling cultural practices to be sustained, are important for local livelihoods.5

These aspects are all affected by how the region’s forest resources are managed and governed. A shared understanding of how forests and biodiversity are defined is necessary if these diverse needs are to be satisfied in an equitable way.

A road in a pine plantation forest in Don Duong, Lam Dong, Vietnam.

Source Wikimedia Commons by FreemanKi. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International.

Defining forests

There are a wide variety of terms used to describe the condition of forests. This often leads to diverging ways of reporting forest cover, forest gain and forest losses. Different land-use preferences can lead to the same section of forest being described by different stakeholders in different ways. The following table6 provides definitions for a range of terms used to characterize forest resources.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Wooded areas | Land that meets all the requirements to be defined as forest, except that it only has between 5% and10% tree canopy cover. |

| Tree canopy cover | The percentage of shaded area below the crowns of trees in a forest, which is used as a measure of canopy density. |

| Secondary forest | Either regenerating or native forests that have been become degraded by natural phenomena or human causes, such as agriculture. Major differences in forest and/or species structure can be seen compared to primary forests. Secondary forests are generally less stable and can be characterised by different stages of growth. |

| Forest regeneration or reforestation | The restocking of existing forests or woodlands, that have previously been deforested by reducing the forest cover to less than that of the definition of a forest. |

| Primary forest | Forests containing endemic tree species, where there are no visible signs of human disturbance to natural ecological processes. |

| Planted forest | Planted forests comprise of both tree plantations of species such as rubber, acacia or eucalyptus, as well as the planted component of semi-natural forests. |

| Plantations | New forest areas established by planting seeds or seedings to create new forest or reforested areas with either introduced or indigenous tree species. They are often managed for commercial timber harvesting. |

| Open forest | A forested area with between 10% and 40% forest cover. |

| Old-growth forest | A forest without a significant disturbance for at least 100 to 150 years, comprising old trees, a multi-layered canopy, the presence of woody debris, as well as standing and fallen dead tress (snags) that provide diverse wildlife habitats. |

| Non-forested areas | Non-forest is not dense forest, mixed forest, water or cloud. Non-forest Areas including urban development, field crops, shrub land, and fallow or barren land, as well as other areas impacted by humans. |

| Mixed forests | Mixed forests are generally dry, mixed, deciduous forests. Theyinclude regrowth forests, stunted forests, mangroves, “flooded” forests, as well as plantations growing bamboo, rubber, acacia, eucalyptus and other tree crops. |

| Forest cover | The amount of land that falls into a particular forest classification. |

| Forest | A portion of land larger than half a hectare (5,000m2) with trees taller than 5 meters with a tree canopy cover greater than 10%, or trees with the potential to meet these criteria. Forests do not include land that is predominantly agricultural or urban. |

| Evergreen forests | Forest comprised of trees that do not lose their leaves through seasonal abscission (shedding leaves). |

| Dense forests | Forests that are mainly evergreen forests, located mostly at elevations above than 500 meters. Dense forests are often also old-growth forests. |

| Deforestation | The conversion of forest to another land use category or a long-term reduction in tree canopy cover to less than 10%. (FAO 2000) Clearing or harvesting timber from forestes areas is not considered deforestation if the land use category does not immediately change. |

| Deciduous forests | A forest comprising mainly deciduous trees, which shed and then regrow their leaves seasonally. |

| Closed forests | A forest with tree canopy cover of 60% to 100%. |

| Canopy | The layer of leaves, branches, and stems of trees that cover the ground when viewed from above. |

| Afforestation | The conversion of land from other land use categories into into forest or land with a canopy cover greater than 10%. |

Monitoring forests

Using forest cover statistics alone as a measure of forest ecosystem health or the effectiveness of forest governance in conserving ecosystem services is problematic. Currently, there is no globally accepted, standard definition of a ‘forest’ and the meaning is often defined based on management objectives.7 The most used definition characterizes forests as land of more than 0.5 hectares with trees higher than 5 meters and a canopy cover of more than 10 percent. This does not include land that is predominantly used for agriculture or human settlements.8

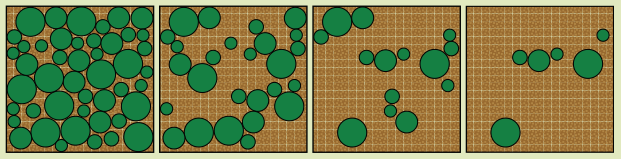

For example, the figure below shows four different representations of 5,000 square meter areas that could be described as a forest by this standard. When changes to the condition of forests within this range occur, they are not detected by this definition.

Forested areas with 70%, 40%, 20% and 10% tree coverage, respectively. These representations would all count as a ‘forest’ in FAO statistics.9

To monitor forests more effectively, changes to their quality need to be considered. This is a more reliable indicator of the capacity of a forest to continue to provide forest products such as timber, food and fuel, as well as a wide range of other ecosystem services. These include carbon storage, nutrient cycling, water and air purification, and maintenance of wildlife habitat, as well as cultural and spiritual services.

For example, detailed assessments of forest cover using high-resolution maps are now able to detect more specific trends in forest cover change such as whether primary forests with high ecosystem function have been lost as a result of reforestation and afforestation programs focused on tree plantations of lower ecological value.10

Geographical information systems using high-resolution satellite imagery are now able to detect and monitor changes to forest cover as it is occuring, with the capacity to remotely collect data more frequently at more local scales.11 This has enabled more accurate accurate understanding of forest trends in the region to be identified.12

Related to forests

References

- 1. WWF 2016. “Mekong River in the Economy”. Accessed June 2018.

- 2. Human Rights Council 2017. “Report of the Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples”. Accessed June 2018.

- 3. Hughes, A. C. 2017. “Even as more new species are found, Southeast Asia is in the grip of a biodiversity crisis”. Accessed June 2018.

- 4. Costenbader, J., Broadhead, J., Yasmi, Y., and Durst, P. 2015. “Drivers Affecting Forest Change in the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS): An Overview” Accessed June 2018.

- 5. Yasmi, Y., Durst. P., Haq, R.U. & Broadhead, J. 2017. “Forest change in the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS): An overview of negative and positive drivers”. Accessed June 2018.

- 6. FAO 2015. “FRA 2015: Terms and Definitions”. Accessed February 2018.

- 7. Venkateswarlu, D. 2013. “Definition of Forests: A Review”. Accessed February 2018.

- 8. FAO 2015. “FRA 2015: Terms and Definitions”. Accessed February 2018.

- 9. FAO 2011. “Forests and Forestry in the Greater Mekong Subregion to 2020”. Accessed January 2015.

- 10. Center for International Foresty Research 2013. “Use Hansen high-res forest cover maps wisely, experts say”. Accessed June 2018.

- 11. Global Forest Watch 2018. “Forest monitoring designed for action”. Accessed Feburary 2018.

- 12. Yasmi, Y., Durst. P., Haq, R.U. & Broadhead, J. 2017. “Forest change in the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS): An overview of negative and positive drivers”. Accessed June 2018.